Part of this identity crisis was bad timing. Modernist jewelry is squeezed in between Art Deco and the 1940’s, and sometimes contains elements of either of these. Back when jewelry of the 1930’s and 1940’s became popular, the auction houses decided to lump these two very different styles together as “Retro”. Although the auction houses obviously wanted to give this jewelry a name that clients could remember, it was an unfortunate and inaccurate choice, and has resulted in a lot of confusion. In fact, I was just looking on Google for 1930’s jewelry, and what came up ranged from Art Nouveau through Art Deco through to the 1950’s, with very few pieces actually from the 1930’s.

Most jewelry books also write about jewelry from Art Deco through the 1940’s, and fail to mention the Modernist style, or even to differentiate jewelry styles of the 1930’s from those of the 1940’s. For starters, jewelry from the 1930’s evolved from Art Deco, and quite a bit of jewelry from the early ’30’s still has a very Art Deco feeling, but by the mid ’30’s, Art Deco was essentially over. Jewelry from the 1940’s took a lot of ideas from Victorian jewelry, but that’s another show! Secondly, neither jewelry from the ’30’s or ’40’s looks back on anything, so why call it by the rather unflattering term “Retro”? The correct name for the most important style of 1930’s jewelry is MODERNIST, and the term “Retro” should be abolished.

Yellow gold, rarely seen since around 1910, was now very much back in fashion, and was now used almost exclusively, although we do still see pieces in white metal. Fluted and swirled gold, highly polished, was now a major stylistic element, and we now see jewelry made only in gold, with no stones.

Geometric forms of Art Deco were often still there, but softened and curved.

Heavy link bracelets, now often called “Contessa” bracelets for their opulent quantity of gold, made use of many different link styles, often combining several kinds of link in one bracelet. The most “Modernist” jewelry, though, usually made use of only one or two elements. When stones were used, they were often rectangular or square.

Other jewelry houses picked up on these two stylistic elements very quickly, and they became very associated with 1930’s jewelry, and continued to be in fashion through the 1940’s.

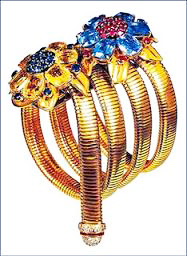

Another major stylistic element of 1930’s jewelry was the“tubo-gaz, “gas pipe” or “passe-partout“. This was first developed by Van Cleef & Arpels, and was made by closely winding thin gold elements so that they attached invisibly to each-other, creating a flexible tube, which could be round, flat, or even have curves. This was very popular for necklaces and bracelets. VC&A had developed the process for producing this, and as they had the necessary machinery, they often made it for other jewelers.It was very effective for either a necklace or bracelet with no stones – a very pure jewelry design. Sometimes, a central element with stones was added, often in the form of a clip that could be removed and worn separately, making is less Modernist, but very beautiful.

Van Cleef & Arpels was especially known for this, using beautiful, stylized flowers, often of yellow and pale blue sapphires.

Different colors of gold were now also seen everywhere. Pink gold, produced by adding copper to the gold, was especially popular, and green gold is also seen. More than one color of gold is often seen in one piece, especially bracelets.

Long sautoires, popular during the 1920’s, were no longer in fashion, with necklaces now sitting close to the neck.

The new, popular stone was citrine – a quartz in the same family as amethyst – in fact, citrine can be created by heating amethyst. Citrine was a very useful stone. It exists in a range of shades from dark, rich orange-brown, known as Madiera citrine, through to very pale yellow. Citrines complimented yellow gold by bringing in sparkle and texture without introducing a new color, giving the jewelry a very harmonious look. It is also flattering to most complexions, and plays well with other colors.

As yellow gold was replacing white gold and platinum (except, perhaps, for formal evening jewelry), the straight lines

They became very popular for both day and evening use, and worked well in yellow gold for less formal wear, and in white metal and diamonds, were stunning for evening wear, clipped to the edge of the dress neckline. Modernist jewelry is not only beautiful — the designs are strong and clean — but also often more “feminine” than the Art Deco jewelry that preceded it.

Heading into the 1940’s, jewelry styles underwent many changes. Victorian elements began to appear, and in order to use less gold, which was now hard to come by because of the war, ruffles of lacy gold were used, as this required less metal. Very large semi-precious stones were in favor, also to compensate for the scarcity of gold.

One thing interesting to note – jewelry of the early 1950’s often looks very much like the jewelry of the late 1930’s – early 1940’s. The explanation? When jewelers returned to their trade after leaving to fight in WW2, they picked-up where they had left off, and it took a few years for the very different jewelry styles of the 1950’s to evolve. In the interests of clarity, I do want to mention that there were other jewelry styles in play during the 1930’s that are quite different.

The House of Boivin was producing beautiful pieces based on nature, such as flowers and animals. Fulco de Verdura was also designing jewelry that referenced nature, along with heraldry and many other motifs, and he also introduced gold twisted to look like rope, and gold tassels were becoming a design feature that would continue through the 1950’s. There were other styles emerging that would become much more prevalent in the 1950’s, but Modernist jewelry, with its simplicity and strong design, remains arguably the most important style to emerge during the 1930’s, and deserves to be recognized as an important style in its own right.

By Audrey Friedman. No portion of the above blog may be used without written permission of Audrey Friedman.

To see pieces of Modernist and other jewelry on our website, please click here.