While one important aspect of Art Deco jewelry is rigorously geometric, and limited in color largely to white and black, with occasional touches of color, there is another major aspect of Art Deco jewelry that is full of curves, set with colorful stones, often carved, and embellished with lushly colored enamels in motifs that reflect many exotic influences.

The reds and purples, greens and oranges of the Ballets Russes sets and costumes jolted eyes that had grown tired of the mauves and other muted colors of Art Nouveau, and of the unrelenting “whiteness” of Edwardian jewelry. These vibrant colors were translated into jewelry set with semi-precious stones, such as coral, amethyst, jade, turquoise, and lapis lazuli, and a host of colorful precious stones. The stones were often carved or fluted for a richer effect. The semi-precious stones created large areas of color and texture, and could be readily carved into a variety of shapes. For the more rigorously geometric jewelry, they were cut into domes, circles, baguettes, squares and other geometric forms, often super-imposed on one-another to create depth and dimension.

Many people, however, as “modern” as they considered themselves to be, were not willing to give up the familiar images that they loved, and naturalistic elements were still very much in evidence in Art Deco jewelry. We still see an abundance of birds, flowers and animals, but instead of the sinuous, flowing lines of Art Nouveau, Nature was now geometrically stylized, captive to new ways of viewing the world.

World War 1 necessitated technological advances, and many of them proved to have great benefits in peacetime. The end of the war also saw many cultural changes both in Europe and in America. Women were enjoying greater freedom, and rejected the cumbersome long skirts and petticoats for lighter, shorter and sleeker garments.

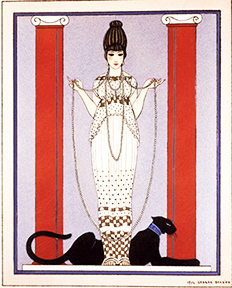

The famed French designer Paul Poiret re-introduced the “Empire” style. New jewelry styles emerged to compliment the new fashions – long chains with a decorative pendant, known as sautoirs became popular, as well as shorter necklaces that filled in an open neckline.

The jabot – a pin with a decorative element at each end connected by a metal rod hidden beneath the garment also became a must-have jewel.

Bare arms cried out for dramatic bracelets, and the new, short hairstyles required hanging earrings to set them off.

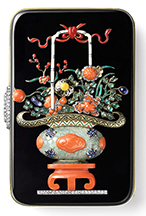

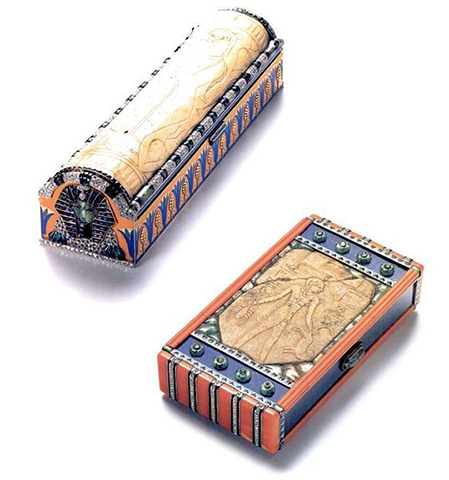

It was now acceptable for women to smoke and apply makeup in public, and a profusion of cigarette cases, compacts, and lipstick cases appeared, so that a woman could engage in these activities with style. The minaudiere was created –a small, purse-like accessory that contained a mirror, face powder and rouge, lipstick and sometimes a place for a few cigarettes or money. The word “minauder” means “to simper” in French, and it was so named for the women making faces as they peered into the tiny mirrors. These compacts and minaudieres gave rise to some of the most beautiful and extravagant jeweled and enameled objects that we see in the Art Deco period. For the less wealthy, all of these things were available made from metal, artificial stones and enamels, and soon, the new plastics like Bakelite and Galilite.

New techniques in watch-making now made possible small movements, so that a watch could be worn on the wrist, or incorporated into a beautiful jewel to be worn on a lapel.

All of these new jewelry styles gave jewelry designers the chance to translate the diverse stylistic influences that characterize Art Deco into beautiful and stylish jewelry for every taste, and we see some of the most exciting, lush and dramatic jewels of the 20th century.

Enamels were now back in fashion, and strong reds, blues and greens could be used to echo the colors of the stones, or to contrast with them in new and sophisticated ways. Black enamel was especially important. Now that it was permissible for women to smoke and apply make-up in public, boxes of various sizes were created for these purposes, and they ranged from the amusing to the splendid. The large, flat surfaces of these boxes provided the perfect canvas for the enamel artist. Polo players, crouching tigers, leaping gazelles and speeding trains could be found decorating these new fashion necessities.

Enamels could also be used to mimic lapis, jade and coral, and magnificent ladies’ compacts were lavishly enameled, and encrusted with diamonds, precious stones, and mother-of-pearl inlays in a dizzying profusion of styles and colors. This very painstaking technique was often done by the Russian master Vladimir Makovsky, and one can find the initial M on his pieces.

In addition to the Ballets Russes, there were other influences that introduced the rich and striking color that inspired so much of Art Deco jewelry design. The early 20th century saw many radical changes in both culture and technology. Increased trade with “exotic” lands brought new and original images into the gene pool of European decorative arts. The influence of Asia was major.

One must keep in mind that for most Europeans and Americans, the “East “ was a very vague and mysterious place. It was a strange, far-away and romantic part of the world that included Russia, Persia, India, Egypt, China and Japan. Decorative elements from all of these cultures found their way into what has become one of the best loved and most sought – after area of 20th century jewelry. Jewelry designers enthusiastically combined “Eastern” elements from various cultures, with a blithe unconcern for their origins, creating jewels that were exuberantly exotic.

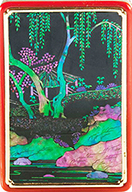

Increased trade with China and Japan gave Europeans the chance to admire the refined esthetics of these cultures. The simplicity of Japanese art and decoration began showing up in the mid-1900’s. Westerners were enchanted by the flowing, sinuous movement, refined palette, flat planes and stylized simplicity of Japanese art, and an entire style, known as Japonisme, emerged in the late 19th century. Art Nouveau, the style that flourished from 1890 until 1910, borrowed much of its esthetic direction from the naturalism and stylization that characterized Japanese Art in Western eyes.

China provided different, if equally exotic images. Red and black enamels were enormously popular, often using elements of Chinese culture associated with long life, wealth, good luck and happiness. Vibrant and dramatic, these colors paid homage to the famous lacquer work associated with China.

Exquisite and precious small boxes were created, ornamented by intricate scenes of life in Imperial China created from inlays of tinted mother-of-pearl. Hanging earrings appeared that looked like Chinese lanterns, and stylized branches of flowers, or scenes from court life could be found delicately displayed on brooches and bracelets.

Jacques Cartier designed and produced some of the most beautiful and important Art Deco jewelry. He was fascinated by Islamic art, and had many volumes of finely bound books on the subject in his library. He based some of his earliest designs on these bindings, and on the imagery that he found within. Beautiful “jardinières”, baskets of rounded vases filled with lush flowers were exquisitely translated into jewelry and objects of every description using diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds, often with touches of enamel. Fountains, birds and animals were given similar treatments. Turquoise, believed by Muslims to protect the wearer from evil, became newly popular. Other jewelers certainly took note of this, and also began using these Eastern elements in their designs. Van Cleef and Arpels, Tiffany & Co., Mauboussin, Boucheron …virtually every jewelry house seized this wealth of fresh and exotic imagery and made it their own.

India also contributed hugely to Art Deco jewelry design. Jewelry forms, such as the bracelet of facing dragons provided endless inspiration.

The Sarpeh, a feathered and jeweled piece worn by noblemen on their turbans was translated into hair ornaments as well as brooch and necklace motifs. Rubies, sapphires and emeralds were carved into dainty leaves and flowers, and had long been an element in Indian jewelry. They had the advantage of making good use of less than perfect stones, and Jacques Cartier used them to create his celebrated and highly sought-after “”Fruit Salad” or “Tutti Fruiti” jewels, named for their glowing assemblage of colors.

Cartier prided himself in being the first jeweler to use such daring color combinations, although other jewelry houses disputed this claim. He also pioneered the use of emerald and sapphire together for many of his Persian inspired pieces, sometimes using stones of impressive size for his wealthy, and often royal, clients. He also claimed to be the first jeweler to combine emeralds with coral. Touches of black enamel, and the brilliance of diamonds brought even more splendor to the already extravagant color combinations.

Arguably, the most important exotic influence on Art Deco jewelry was that of ancient Egypt. Egyptian elements had been popular since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. There was renewed interest following the Franco-Egyptian Exhibition at the Louvre in 1911, but it reached a positive frenzy with the opening of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

The magnificent objects found there were more fabulous than anything anyone had ever seen before.

Advances in publishing made these images available to a general public hungry for novelty. Ancient Egyptian images showed up in every aspect of the decorative arts, and nowhere was this more visible and more strikingly translated than in jewelry design. Actual archaeological artifacts, such as small faience pieces, were often incorporated into a piece of Egyptian Revival jewelry, and can be seen on some of Cartier’s famed boxes.

While an Egyptologist would have had great difficulty deciphering the often randomly chosen hieroglyphics ornamenting a piece of Art Deco jewelry, the public had no difficulty at all enjoying them.

Strongly associated with Art Deco jewelry was the preference for white metal. Historically this had been silver, and then white gold, which was developed after WW1. The most important new white metal for jewelry, however, was platinum. Platinum had previously been little used in jewelry because of the technical difficulties of working with it. It has a melting point of around 1,770 degrees, and can also be brittle. Russian jewelers had found ways of working with it – they had developed an oxy-acetyline torch, or something similar, by the late 19th century.

There are varying stories of who actually invented the oxy-acetylene torch and where, but able to reach temperatures of 3000 degrees, it could be used to melt this seemingly intractable metal. By the beginning of the 20th century, many jewelers were experimenting with and perfecting its use. Why was this so important? Because of its hardness and tensile strength, it could be very finely worked, allowing much more refined and less conspicuous stone settings.

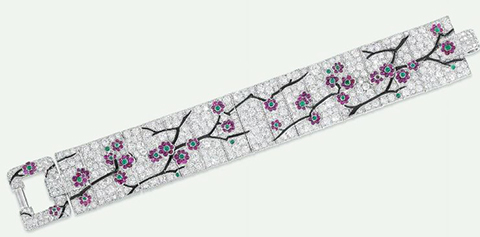

This led to the development of “pavé” work in which the stones could be set so closely to each other as to create, literally a “paved” surface of diamonds in which the settings are all but invisible. The effect was a solid area of sparkle. Colored stoned could also be “pavé” set, creating an unbroken expanse of shimmering color, with no metallic intrusions to disturb the eye.

In addition to the above, platinum made possible an important new development in jewelry design – the ribbon bracelet. It’s broad. flat links were seamlessly integrated to appear as one surface – a “ribbon”, usually of small, pavé set diamonds, which provided the perfect foil for the pictorial images that these exotic influences inspired.

While platinum was important for creating strong, almost invisible settings, it is not an especially beautiful metal, , and white gold, warmer and more attractive, was usually used for the body of a piece.

Revolutionary developments in stone cutting also contributed to the excitement of Art Deco design. Colored stones were now being cut “en calibré”. This was a very painstaking technique in which each stone was carefully cut into rectangles, squares, triangles, and often odd shapes to fit perfectly next to it’s neighbor, thus creating an unbroken line of color. The tops of the stoned were polished, with either subtle facets or a domed cushion surface.

In this way, a jewelry designer could “paint” with stones on the bright, white surface of platinum and white gold with small sparkling diamonds as the background.. Delicate branches of blossoms in the Japanese taste, scenes of Ancient Egypt, and bold geometric designs could flow unimpeded across the surface of a bracelet or brooch.

This great diversity of styles that we lump under the term Art Deco often leaves people confused as to what “Art Deco” jewelry really looks like. The most important hallmarks of Art Deco jewelry, however, and the ones that have continued to make Art Deco jewelry so sought after by collectors today, it the powerful simplicity of the Cubist inspired pieces, and the explosion of color and exotic influences, used in new, exciting and artistic ways.

By Audrey Friedman

Copyright protected, no part of the text of this article may be used without consent of Audrey Friedman.