(British, 1921-2007)

LITERATURE: Modern Jewelry, by Graham Hughs

Twentieth Century British Jewelry 1900 – 1980 by Peter Hinks

GRIMA RETROSPECTIVE, Goldsmith’s Hall, 1991

GRIMA, by Johann Willsberger, 1991

grima-pendant-with-watermelon-tourmalines.jpgI consider myself privileged to have known Andrew Grima, his wife Jojo, and his daughter Francesca personally. A number of years ago, Andrew had learned that we were showing his jewelry at Primavera Gallery, and telephoned us from Gstaad, where they spent a lot of time, and had a shop. When I told him that I would be in Geneva soon for the jewelry sales, he offered to send a car to bring me to Gstaad, and then take me back to Geneva. It was a lovely visit – the chic and elegant shop, the fabulous scenery, and, of course, Andrew Grima’s jewelry. It was a lovely day, and a pleasure to get to know them.

Thereafter, if we were all in London at the same time, they would always invite me for lunch at their flat, or for dinner. Lunch was always smoked salmon from Fortnum & Mason – just across the street, and champagne. Dinner was always at Gavroche. I would go through trays of Andrew’s jewelry, and choose as many pieces as I could. I was deeply saddened when he passed away, but he had a remarkable life.

Andrew Grima was born to a Maltese father and an Italian mother in Rome in 1921. He moved to London at the age of 5, and graduated from Nottingham University. After nearly five years as an engineer with the 5th Indian Division in Burma, he returned to England with no definite idea as to what career he wanted to pursue. His came to jewelry design rather by accident – he was never formally trained. When Andrew returned to London after the war, he worked as an administrator for his then father-in-law’s company, a small jewelry workshop specializing in jewelry exports to Latin America and South Africa known grima-tanzanite-ring.jpgas H.J. Company. Heavy import restrictions and very high British purchase tax eventually made their continued business very difficult, and they moved to re-styling older jewelry. Andrew took over the business completely in 1951 upon the death of his father-in-law.

Also in the early 1950’s, Andrew went into business with a Michael Gottschalk to design and produce jewelry to compete with the Italian jewelry then flooding into England. Gottschalk subsequently moved to France in 1963, and Grima continued in the jewelry business with a new firm – Hooper Bolton, and it was there that Grima finally had the opportunity to really begin express his talent as a jewelry designer.

He had persuaded his father-in-law, years before, to buy a suitcase full of semiprecious stones from two Brazilian dealers. Andrew had then wanted to design “a new kind of jewelry” with the large and beautiful aquamarines, amethysts and citrines. Little did he know at that time that with grima-coral-bracelet-and-ring.jpghis great artistic gifts, he would revolutionize jewelry design, and the name Andrew Grima would become famous for stunning and original jewelry.

Grima had always been interested in painting, and was a prolific painter. He was inspired to design jewelry after visiting an exhibition of contemporary painting and sculpture in 1961, given by The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. He approached jewelry design with his new esthetic vision. He wanted to break with existing design traditions, and explore more organic aspects of design.

He preferred gold to silver, but was interested in the white gold alloys being developed, and used them in pieces where he wanted a white metal. Now he could fully explore the possibilities of the unusual colored and textured semi-precious stones, as well as pearls, which he continued to prefer for both esthetic and financial reasons over usual formally-cut precious stones. When he did employ precious stones in his designs, they were usually intended to add contrast and interest, and not to be the main focus, but he did, on occasion, use the less precious light colored grima-crystals-pin.jpgemeralds and sapphires in his designs. With regard to diamonds, almost every piece he designed had a small diamond incorporated into the design. Andrew explained to me that this was to bring light and a bit of sparkle to his jewelry.

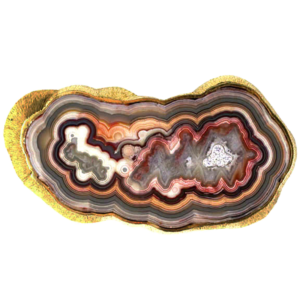

Grima experimented with materials. He developed a technique of working with gold wire to produce an undulating surface that reflected light in a beautiful way. He also loved materials found in nature, and developed new techniques for casting delicate materials. He did castings of leaves in gold, to which he would add a small diamond. He did a casting of an interesting lichen, which became a favorite brooch of Princess Margaret. I had begged him to make one for me, but, alas, it never happened. He loved texture, and this is a hallmark of his designs, and soon to be seen everywhere in jewelry of the 1960’s. Grima was also among the first jewelry designers to use raw minerals in his pieces – sometimes slices of geode, with the protruding crystals forming a contrast to the polished surface. He also admired beautiful agates, and did several brooches using this material.

grima-gold-wedding-ring.jpgGrima’s jewelry designs became increasingly popular in the 1960s. His jewelry was highly original, and bold in both scale and concept. It was different sometimes even flamboyant jewelry for the modern, independent woman with a strong sense of herself, who preferred these large and striking jewels to the more mundane designs being produced by most jewelers.

During the 1960’s, Grima won twelve De Beers Diamond International Awards, and in 1966, designed a brooch of rubies and diamonds in free-form gold that Prince Phillip gave as a gift to Queen Elizabeth. It was such a success that he was awarded the 1966 Duke of Edinburgh’s prize for elegant design, and the Queen’s Award for Industry. Also in 1966, he opened a very modern and architecturally quite interesting gallery on Jermyn Street in London, and also received the Queen’s Royal Warrant, which he held until he closed the Jermyn Street shop and moved to Gstaad in 1986, when he founded FARNESE SA in Lugano. During the 1970’s, Grima also opened jewelry galleries in New York, Sydney and Tokyo.

Andrew Grima was a man of great charm as well as talent, and had numerous well-known clients. One very important client was Lord Snowdon. Lord Snowdon had written an article in the paper saying that there was nothing exciting in jewelry,” Grima’s wife said. “My husband called and said, grima-mop-brooch.jpg’Would you like to come and see my workshop,’ and they became good friends.” After this meeting, Snowdon and Grima formed a long lasting friendship, which resulted in Grima’s appointment as a jewelry maker to the British royal family. In fact, the day before Andrew Grima passed away, Queen Elizabeth II wore the ruby, diamond and gold brooch for her televised Christmas Day speech.

Grima’s famous customers, in addition to the British Royal family, included First Lady Jacqueline Onassis, actress Ursula Andress and sculptor Barbara Hepworth. He also had a large following in the United States.

One of Andrew Grima’s most important commissions came from the watch company Omega in 1969, when he was commissioned to create a very

grima-brooch-w-amethyst.jpg

special collection of watches. The collection was cleverly titled ABOUT TIME. It consisted of 85 pieces – fifty watches and thirty-one matching pieces. For the watches, each had a crystal made from a semi-precious stone, rather than glass. Creating the collection required 64 craftspeople, and took a year to complete. It was exhibited to great acclaim in many venues around the world. Grima said it was “the greatest challenge of his career”.

The auction house Bonhams described Grima as “a designer who revolutionized his craft and

“changed the way jewelry was looked at and worn by the public.”

Andrew Grima died December 16, 2007, at the age of 86. His designs were extremely influential throughout his lifetime, and continue to provide inspiration for jewelry design today.

Showing all 5 results

-

$4,000,050.00

-

$4,000,050,000.00

-

$1,000,020,000.00