LITERATURE: The Encyclopedia of Art Deco, Edited by Alistair Duncan

Art Deco, by Victor Arwas

In 1875, Jean Daum took control of operations at a glassmaking company in Nancy, France. The glass factory, the first to be established in the region, was known from its inception until World War II as the “Verrerie de Nancy.”

In 1879 Auguste Daum took over his father’s business, and in 1887 brought his brother, Antonin, in to work with him. In 1889, the Daum brothers made the decision to open a decorating studio, inspired by the art glass of Emile Gallé and the success which he achieved at the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition. These two firms – Gallé and Daum – became the founders of the Ecole de Nancy, which would become increasingly famous as the source of artistic glass in France.

In their decorating studio, the Daum brothers produced pieces which were both artistic and utilitarian. Over time, however, they began to concentrate on more aesthetically interesting work, and by 1893, they were exhibiting at all the great exhibitions, showing pieces that combined creative spirit with technical perfection.

By 1900, Daum had found its own style, taking inspiration from nature. They did several series of small but charming pieces with shallowly cut and enameled scenes of winter, spring, rain on flowers, and delicate floral motifs. Their larger pieces were also often acid cut, with scenic views or flowering plants, and they did several exceptional pieces that were hand-blown and decorated to look like gourds, very much reflecting the influence of Japonism on the decorative arts at that time.

Going into the 1920’s, the taste for Art Nouveau and Naturalism was waning, as the strong colors and geometric shaped of the newly emerging Art Deco was now the style. The Daum brothers began using such technological advances as very deep acid etching, and wheel engraving, previously used for naturalistic details, was now used to achieve subtle surface variations including the “martele”, or “hammered” effect. These skills would serve them well for creating the subtle textures that would be used to enhance their later pieces.

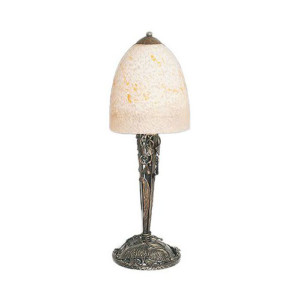

The style of glass made after WW1 began to show dramatic changes. Influenced by the work of Mauric Marinot, their forms became more formal, and the glass walls quite thick – all the better to transmit interesting light effects through the various surface treatments of the glass. Often, flecks of silver or gold metal were mixed into the glass, reflecting light and adding a subtle sparkle.

Daum began to use acid for “deep” cutting. To achieve this relief decoration on glass, the Daum decorator took a brush saturated in Judean bitumen and painted the design on the glass. He then immersed the glass into an acid bath. This process, in order to get the required affect, had to be repeated a number of times, depending on how deeply cut the area was to be. They varied the depth of cutting to create different effects of light transmission, often using several variations on a single piece. In fact, when one examines a deeply etched piece of Daum glass, it is possible to see how many times it was dipped into the acid bath. This was a difficult and dangerous technique. The acid was very corrosive, most probably muriatic acid, and the glass blanks were often quite large and very heavy, leaving many opportunities for serious accidents, and the technique was eventually banned by the French government. The last step was to dip the glass in turpentine to remove all traces of the bitumen.

After the acid baths, the pieces were further refined by having various textures carved into the acid-cut areas by hand, using various engraving wheels. The areas un-touched by the acid remained smooth and shiny, creating a strong contrast of sleek smoothness and subtle texture. The most interesting pieces focused less on naturalistic figures and more on stylized and geometric forms, which were the hallmarks of Art Deco design.

Daum’s vases of the Art Deco period, unlike their earlier glass, were monochromatic in color. They favored smoky taupe, deep grays, and rich browns, but also made very effective use of clear blues, greens, orange, pale purple, yellow, and even clear, colorless glass, which was very effective when given various frosted textures. What is so intriguing and striking about Daum’s glass are the ways in which it transmits light to create a monochromatic motif of texture. The light passing through each layer is affected differently by both the texture and the thickness of the glass, and this brings complexity to the piece. The use of the one color and simple, strong forms give the pieces a strong, sculptural presence. Inclusions of metals or other colored materials into the body of the glass added further interest.

Going into the 1930’s, the pieces became thinner walled, with less complex designs and shallower acid cutting. These were easier and less costly to produce, but lack the drama and technical complexity of their earlier pieces.

Daum Frères greatly expanded on ideas first presented by Maurice Marinot, and produced pieces of strong design and great decorative power. Their best pieces are dramatic and elegant studies in texture and light.

Showing all 11 results

-

$0.00