Born in 1915 to Emo and Alvira Bianconi, Fulvio Bianconi showed an early predisposition to drawing and caricature that would eventually lead him to attend the Istituto Statale d’Arte Carmini and later the Accademia de Belle Arte in Venice (Fulviobianconi.com; Mentasti 110). In his more than sixty years of artistic activity, he designed thousands of books, produced innumerous illustrations and paintings, and designed and created thousands of glass objects. Between the ages of sixteen and seventeen, he apprenticed at the famous Murano furnaces, which would have a profound impact on his future evolution as an artist. Until 1946, Bianconi produced illustrations and cartoons for the Italian Ministry of Popular Culture, and after the end of World War II worked as a graphic designer for various Italian publishing houses (Fulviobianconi.com). His background in caricature and his love of drawing provided him with a playful and gestural aesthetic.

Bianconi’s real contribution to the world of art and design, however, finds its inception in 1947 when the Milanese Paulo Venini commissioned a series of perfume bottles from the illustrator, beginning the artist’s career as a freelance glasswork designer (Ricke 22). Unimpeded by the restrictions of the glass artisan’s principles of design and financially independent due to his work as a graphic designer, Bianconi was free to experiment with the formal qualities and potentials of glass as a fluid and organic medium. His earliest freelance work for Venini, which he not only designed but also cut and ground himself in order to become familiar with the medium, engages in a spontaneous aesthetic that intentionally and ironically protests against traditional values of perfect craftsmanship (Ricke 23). Throughout the late 1940’s and 1950’s, Bianconi brought a theatrical and humorous sensibility to his glasswork design that was born both from his personal roots in cartooning and caricature as well as a more general atmosphere of creative experimentation enjoyed by a post-Fascist Italy (Bossaglia 7-8; Ricke 22).

There is an immediacy and flamboyancy in his aesthetic that betrays a cartoonist’s taste for the gestural, achieved through an improvised and freehand manipulation of glass while in the furnace. Rather than engage in the tradition of perfect repetition that had so long denoted artisanal excellence, Bianconi instead injected the individuality and expressivity of the caricaturist’s hand into his glasswork designs. “The artistic glass,” wrote Bianconi, “must be unique, if it is repeated it loses its charm” (Fulviobianconi.com). Though his idiosyncratic designs oftentimes brought him into direct conflict with the more restrained sensibilities of master Muranese glassworkers, it is exactly this freedom from traditional constraints that would lead Bianconi’s designs to have such a lasting influence.

Paulo Venini recognized Bianconi’s potential and fed it through continuous freelance commissions. In 1948, Bianconi finally found a sympathetic creative partner in maestro Arturo “Boboli” Biasuttro, whose realizations of the designer’s twelve Maschere della Commedia dell’Arte for the 1948 Biennale brought him a new critical success and popular influence in the realm of glass design (Mentasti 110). While the human figure was by no means a novel subject of glass design, Bianconi’s masked figurines exhibit a concern for chromatic contrasts and brush up against a playful abstraction that gave them a fresh and vivacious flavor (Mentasti 110). He created stylized nude figures in clear, flesh-colored glass, and also made a series of vases with a very feminine form.

An initial love for color and tendency towards abstraction would characterize the direction of Bianconi’s further creative evolution in the realm of glasswork. As he gained increasing confidence in his value as a designer, Bianconi reveled in the medium’s expressive potentials, and began to wholeheartedly utilize the luminosity of glass to develop intensely colorful displays that are almost painterly. Indeed, while form is always an essential part of Bianconi’s design, it is most often color that comes to the forefront as the true subject of his work.

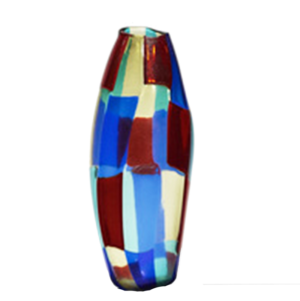

This is particularly true of his Pezzato series, designed in 1950 and first displayed in the 1951 Triennale (Mentasti 110). Here, irregular patchworks of colored tesserae are fused in a seeming reference to both the theatricality of the harlequin’s outfit and Paul Klee’s work of the 1920’s and 1930’s (Ricke 23).

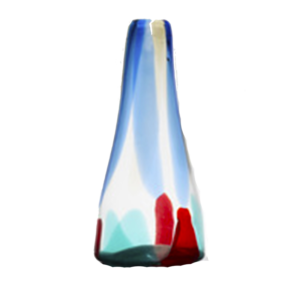

Bianconi further developed his chromatic vocabulary in a series of vases featuring overlapping bands of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal colors that were exhibited in the 1952 Biennale (Mentasi 110). Both of these series play with glass’ capacity for both transparency and opacity, as well as the way in which a contrast between the two may serve a sense of fluidity and spontaneity.

Bianconi was also one of the only glass designers who adapted trends in contemporary art into his work, as in the Macciato (stained) pieces, which are quite rare, and also in vessels that use applied lines of colored glass and splashes of enamels.

The strength of Bianconi’s designs lies in the illusion of haphazardness that they exhibit. His financial independence allowed him to design under the guidance of personal intuition and with the freedom of a hobbyist. But it is only a solid grounding in technical ability that allowed this draftsman-turned-designer to create such seemingly effortless works. This, then, is the true beauty of Bianconi’s glasswork: the successful tension between the joyful and innocent desire to create, and the technician’s ability to do so effectively.

Bianconi passed away on May 14th, 1996, in Milano, Italy.

Aaron Mayper for Primavera Gallery

Showing all 4 results