1902 – 1988

There have been many important French designers associated with Art Deco and through the 1930’s, ’40’s and beyond who worked in wrought iron. One usually thinks of Edgar Brandt, Raymond Subes, and Paul Kiss. For quite a while, when Art Deco was enjoying its first flush of recognition in the 1970’s, Gilbert Poillerat remained relatively unknown. This would soon change as the natural progression of design exploration began to move into the 1930’s and beyond, and Poillerat would emerge as one of the most original and important designers of his time.

Gilbert Poillerat was born in 1902 in a small town in France that, oddly, had three names – Mer, Loir et Cher. Like many other furniture designers, he attended the famed École Boulle, where he trained as a metal chiseler and engraver, graduating in 1921.

Following his graduation, he worked with arguably the best and most influential wrought-iron master – Edgar Brandt. He worked for Brandt for over seven years in both design and production. There can be no doubt that this time was hugely important, not only in furthering his training and perfecting his technique, but also exposing him to the new ideas that had blossomed forth during the Art Deco movement, when wrought-iron escaped the constraints of tradition that had kept it static for so long.

In 1927, Poillerat left Brandt, and began working for Baudet, Donon and Roussel, a firm specializing in construction frameworks. He was placed in charge of their decorative iron-work division, which produced tables, screens, grilles, andirons and lighting. This was the perfect opportunity to hone his skills, and also to evolve his own styles.

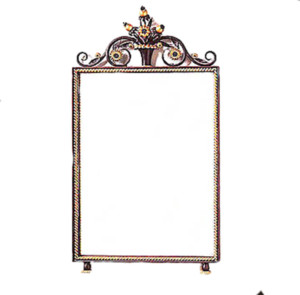

Whereas many of the other important wrought-iron designers incorporated flowers, birds and other images from Nature into their work, Poillerat’s work was closer to calligraphy, and was quite original. In 1928, he first exhibited at the salon d’Automne. His earlier works were studies in fluidity, with complex intertwining of wrought iron in his “calligraphic” style, and often, the wrought iron was gilded.

In 1934, he decided to try his hand at jewelry (the famed American wrought iron artist Albert Paley has similarly made some very jewelry). Poillerat was designing jewelry for the famed French couturier Jacques Heim. In 1935, he was commissioned to design the First Class pool and patinated doors for the ocean liner Normandie.

During this time, though, Poilleral was busily at work designing all manner of furniture and other architectural elements. Tables and consoles were particular specialties, but he also designed table and floor lamps, hanging fixtures, and grilles intended for various purposes.

Poillerat drew inspiration from many sources. He was interested in historical architecture, and one can find elements of Rococco, Directoire and Louis XIV. While he did not embrace floral motifs, he did find elements in Nature to work with, such as massive branches, sun-bursts, corals, leaves, and in several stunning pieces, the skull of an antelope. These were often twined with twisted ropes of iron and tassels, which were a favorite motif of his. One also finds shells, feathers and fluted cups in his furniture designs

Often, he would embellish a piece with metal worked and gilded to look like draped fabric, and globes astrolabes and stars were also used abundantly in his designs, as were complex entrelac designs. Many of his pieces have a distinct Medieval feeling, with suits of armor, and ornate bows and arrows. He selected beautiful marbles to compliment his tables and consoles. In fact, his repertoire of design motifs was so extensive as to almost defy description, but everything he did was marked by his very distinctive personal style.

Poillerat collaborated with many of the leading designers of his time, among them André Arbus, Jean Pascaud, and Vadim Androusov, and his out-put ranged from domestic interiors to museum exteriors.

In 1946, Poillerat left Baudet, Donon et Roussel, and he was named professor at the esteemed École National des Arts Decoratifs, where he taught for 26 years, while continuing his prodigious output.

Moving into the 1950’s, Poillerat’s designs, in keeping with changing tastes, became much simpler and more severely rectilinear, relying on perfect proportions for dramatic effect, and he continued to remain an important figure in French design.

Showing all 5 results