(1889 – 1980)

LITERATURE: JEAN DESPRÉS by Melissa Gabardi; ART DECO JEWELRY BY Sylvie Raulet; Jean Després, by Flor de Brantes

Jean Eugene Gilbert Despres was born in Avallon, a small town in Burgundy, where his parents had a small shop selling jewelry and gifts. At the age of 16, he went to Paris to apprentice with a friend of his father, who had a jewelry and metal workshop in the Marais. At night, he studied design. Any spare time was spent in Montmartre, where he met Modigliani, Soutine, DeChirico, Signac, and most important, Georges Braque, who, with Picasso was the founder of Cubism. Despres and Braque became great friends.

This happy period came to an end with the start of WWI. Despres found employment making aircraft parts, and this would have a great influence on his later jewelry designs.

After the war, he returned to Avallon, where he began designing original jewelry in silver, both to take advantage of the new taste for white metal, and to produce jewelry that would be affordable. The pieces that he designed were quite unique and avant-garde. He designed and made every piece himself, as he had become an accomplished artisan, and is perhaps the only “studio jeweler” of the Art Deco period. The workmanship of his pieces, especially the more complex earlier pieces, is outstanding.

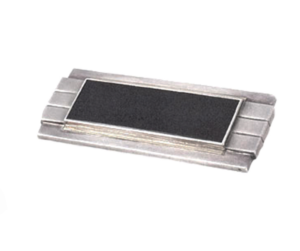

Després had no interest in precious jewelry. When he used gold at all, it was in thin sheets applied to the silver for color contrast. His jewelry designs are strong, some almost brutal. The most conceptual were based on actual machine parts – the influence of his work during WW1. His earlier designs were also strongly Cubist, and he used semi precious stones such as coral, chalcedony, onyx, malachite and lapis for color. He sometimes used enamels to add contrasting geometric elements, but also made great use of enamel to create his designs, using no stones, especially for rings.

His jewelry perfectly expressed the new esthetic of the time. He participated in a number of exhibitions, and his jewelry was very well received.

His revolutionary jewelry designs were of three types – “bijoux glaces”, “bijoux moteurs”, and “bijoux ceramique”.

The “Bijoux-glaces”, done between 1929 and 1937, incorporated small, Cubist paintings that were reverse-painted on glass by the Surrealist artist Etienne Cournault. The mountings were enameled to compliment the miniature images. Josephine Baker was quite taken with them, and one brooch, which depicts a dancing figure, was most certainly of her.His “bijoux-moteurs” created quite a stir when they were shown in 1931 at l’exposition de l’Aviation et l’art moderne, held at the Pavillion de Marsan du Louvre. Bracelets, rings, and brooches were designed to look like connecting rods, cog-wheels, and gears. These jewels represented the height of his creative inventiveness. They echoed images in Fernand Legers’ paintings, and were much admired by the new breed of modern, emancipated women.

Desprès enjoyed using unusual materials in his jewelry. In 1937, he designed a series of pendants, necklaces, bracelets and pins that incorporated ceramic medallions in the neo-classical style executed by the ceramicist Jean Mayodon.

He was nick-named “the Picasso of jewelry work”, and exhibited in all the important national and international exhibitions, and won numerous prizes. His work was appreciated by, (and purchased by) many important writers and artists- Anatole France, Paul Signac, Francois Pompon, the influential critic and curator Andre Malraux and more recently, Andy Warhol, who was an enthusiastic collector of his jewelry and boxes.

Moving on through the 1940’s, 50’s and into the 1970’s, his work became somewhat less complex, relying more on a hammered surface with perhaps a simple motif, and he also produced some interesting pieces in 18k gold, but most of the later pieces do not have the originality and power of his earlier designs.

Despres was also a very prolific designer of useful objects, including all manner of pieces for the table, including vases, tea and coffee services, flatware, trays, candelabra, pitchers, serving pieces and much more. The earlier of these pieces are quite severely geometric, and show great restraint in their design, often relying on only a hammered surface for textural interest.

Moving into the 1940’s, he introduced a design feature that was perhaps a bit more commercial, but gave his pieces great chic – the addition of a heavy link chain called “gormette”. This adorned many of his pieces, and played very well against both polished and hammered surfaces, and these pieces were in great demand, and remain so today.

Showing all 9 results